"Second-rate soldiers": Why prisoners from the ATO and JFO periods are denied the right to demobilization.

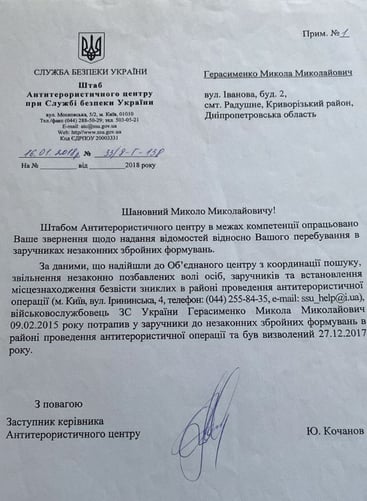

“In 2018, when I and other guys received this certificate from the SBU, we immediately said it was incorrect because we are military personnel who were captured by the enemy. They responded that they could not issue another certificate. In 2024, I finally resigned from the army, but not as a former prisoner, rather as a person with a disability. It hurts me deeply that now in Ukraine, it seems like there are two types of prisoners of war - the 'correct' ones who were captured after February 24, 2022, and the 'incorrect' ones like me, who suffered for almost three years in the basements of the 'DPR.' I was shot at there, had my skull fractured, my ribs broken, and they wanted to condemn me. So, does that mean none of this ever happened in my life?” – says Nikolai.

Why do military personnel who were held captive in the occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions before the full-scale invasion today lack the status of prisoners of war, and therefore, the right to be discharged from the army? Will there be any changes regarding this issue? Hromadske sought answers from military personnel, lawyers, and members of parliament.

In Captivity of Statuses

“Before discussing the status of soldiers captured by the enemy, it is essential to consider the context of certain events. In April 2014, following the onset of Russian aggression against Ukraine, an anti-terrorist operation (ATO) was declared, not a war under martial law. From a legal standpoint, we were, so to speak, dealing with terrorists in eastern Ukraine, not an enemy army. Terrorists take hostages, not prisoners of war. That’s why fighters who were essentially held captive in the 'DPR/LPR' officially received the status of hostages in Ukraine. Although the meaning of the term 'hostage,' as defined in the Law of Ukraine on Counteracting Terrorism, hardly corresponds to the situation of our military personnel. In February 2022, martial law was declared in Ukraine, so military personnel captured after this date have the status of prisoners of war,” – explains lawyer Oksana Dogoter from the law firm 'Aktum.'

According to her, even though we are essentially fighting the same enemy post-2022, legally there are two different statuses for Ukraine regarding events and their participants.

For instance, the head of the medical service of the Azov brigade, Yevgeny Chudnetsov, who has been defending Ukraine since 2014 and was actually captured twice – from February 2015 to December 2017 and from May 2022 to July 2023 – is legally recognized as having been captured only once.

“Journalists often ask me to compare the conditions of captivity before 2022 and after. But I can only speak for myself. Yes, during my first captivity, I could receive food packages from home, make phone calls, and have visits from relatives. During my second captivity, none of this was allowed. I was severely tortured during the second time, and I lost almost half my weight. But my teeth were pulled out with pliers during the first captivity when I was considered a hostage. The facts of torture and humiliation occurred in both the first and second captivity,” – shares Yevgeny.

He states that the issue isn’t about the conditions of captivity or when Ukrainian soldiers were tortured more – before or after 2022, because overall, hostages and prisoners are absolutely equal individuals.

“Why are they legally treated differently? I don’t understand why hostages were not automatically equated to prisoners of war,” – questions Chudnetsov.

So why not amend the relevant article of the Law of Ukraine on Military Duty and Military Service, 'On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Specific Issues of Military Service, Mobilization, and Military Registration,' to include 'was a hostage' in parentheses after 'was in captivity'?

Could it have been possible to automatically equate military personnel who were hostages to prisoners of war, and is the option of 'in parentheses' feasible? Hromadske asked member of parliament Solomiya Bobrovska, a member of the Verkhovna Rada Committee on National Security, Defense, and Intelligence. In 2023-2024, she actively advocated for the rights of former captives to demobilize.

“I was unaware of the existence of the demobilization issue for hostages. You are the first journalist to approach me regarding hostages from the ATO and JFO times. Neither the Security Service of Ukraine nor the Ministry of Defense communicated with our committee on this matter. None of the military personnel who were former hostages raised this issue with us. This problem seems to have fallen off the radar. I don’t think it will be possible to automatically equate hostages to prisoners of war. I need to study this issue and understand it better,” – Solomiya Bobrovska commented for Hromadske.

We then addressed the same question to the SBU. They officially replied that the legal and social protection of hostages requires legislative regulation.

While Deputies Contemplate

Will the Verkhovna Rada Committee on National Security, Defense, and Intelligence immediately tackle the issue of military personnel who were hostages, and will it be resolved positively? No one can say today. So, what should these hostages do if they wish to demobilize? Look for other reasons for discharge like Nikolai Gerasimenko? For those unable to do so due to disability – perhaps have a third child or care for elderly relatives?

“Not at all,” – says lawyer Oksana Dogoter. – They have a legal opportunity to demobilize specifically as former hostages. They just need to be patient,” she adds.

According to the lawyer, the first thing a soldier needs to do is obtain a certificate from the SBU stating that during the ATO and JFO he was a hostage.

“The document that Nikolai Gerasimenko and other hostages received from the Anti-Terrorist Center at the SBU is essentially an informational letter, as the format of the certificate and its content are prescribed by the relevant Procedure. To confirm the fact of being held captive, a certificate is required as a specific type of document defined by law. The Anti-Terrorist Center's successor is the Coordinating Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War. If a military personnel did not receive such a certificate earlier, today he has the right to apply to the Coordinating Headquarters for one,” – explains the lawyer.

This certificate serves as a basis for discharging military personnel from service.

For its part, the SBU informed Hromadske that to obtain a certificate regarding being in places of unfreedom due to armed aggression against Ukraine, a person (or their legal representative) must submit an application to the Ministry of Defense or another central executive authority responsible for military formations. Additionally, former hostages may contact the Commission for establishing the fact of deprivation of personal freedom due to armed aggression against Ukraine, functioning under the Ministry of National Unity of Ukraine (formerly the Ministry of Reintegration).

“The regulation for the commission does not limit the period within which it can establish the facts of the beginning and end of captivity, meaning such a commission can establish facts during the ATO period. Therefore, for military personnel with a similar informational letter from the Anti-Terrorist Center at the SBU, like Nikolai Gerasimenko, this specific state procedure is also accessible,” – notes lawyer Oksana Dogoter.

The document-decision of the Commission for establishing the fact of deprivation of personal freedom due to armed aggression against Ukraine also opens the path to demobilization for military personnel. As stated in Article 26 of the Law of Ukraine on Military Duty and Military Service, being held captive is a valid basis for discharge. The commission's decision is included in the list of documents required to confirm the fact of a military person being held captive, as established by the Procedure for discharge from military service.

If a military personnel who was a hostage submits a discharge request to the command, he must attach the certificate from the Coordinating Headquarters or the decision from the Commission for establishing the fact of deprivation of personal freedom due to armed aggression against Ukraine.

“There can be various situations. For example, the content of the certificate from the Coordinating Headquarters and other documents may not be sufficient for the commission under the Ministry of Unity to make a positive decision regarding a specific soldier. The commission only works with the documents provided, analyzing what the applicant presents, and cannot collect evidence independently – for instance, interview witnesses. In this case, a former hostage may reapply to the commission, increasing the volume of evidence. If the military personnel still receives a decision from the commission denying the establishment of the fact of deprivation of his personal freedom due to armed aggression against Ukraine, he may appeal to the court for protection of his rights,” – says lawyer Oksana Dogoter.