"Despite the shelling, they come here for tours." Discover how the museum in Baturyn is thriving after rising from the ashes of Russian attacks.

Currently, Batyrin is home to just over 2,000 residents, and the city resembles more of a village. However, in the 17th-18th centuries, it was the capital of the Hetmanate with a population exceeding 10,000. This was before the Russians arrived, a little over a hundred kilometers away.

When the Great Northern War began between the Tsardom of Moscow and Sweden, the then-hetman Ivan Mazepa fought alongside Peter I with his Cossacks. In 1708, he decided to switch allegiance to King Charles XII, as the Tsar effectively refused to protect Ukrainian lands.

Upon learning of this, Peter I ordered the complete destruction of Batyrin and the execution of all its inhabitants as an act of revenge. Estimates suggest that the Russians killed up to 15,000 people here, including those Cossacks who valiantly defended the capital until the end.

A few years later, another hetman, Kirill Razumovsky, resurrected the city. He was destined to become the last head of the medieval Cossack state. He made Batyrin the capital again and built himself a substantial palace and the Resurrection Church in his later years, where he was buried after his death.

After the last hetman's death in 1803, Kirill's son, Andrei, moved into the palace. He owned the palace until his death in 1836, but ten years prior, the castle suffered a massive fire causing significant destruction. Following Andrei Razumovsky's passing, the palace fell into ruin, and Batyrin remained an ordinary provincial town.

Concerned descendants of Kirill Razumovsky aimed to restore the palace. His great-grandson, Kamil, living in Austria-Hungary, allocated funds for its renovation with the intention of establishing a Museum of Folk Art there. However, this was thwarted by the turmoil of World War I and later by the 1917-1921 revolution. In 1924, the palace was again struck by a large fire.

Other monuments from the Cossack era also suffered at the hands of the communists. In 1927, Oleg Poplavsky, the head of the Konotop Local History Museum, arrived in Batyrin with an expedition team and ordered the opening of the crypt where Razumovsky's body lay. From there, they stole the heart of the last hetman and concealed it, and its whereabouts remain unknown to this day.

Efforts to restore the memory of the former hetman capital began in the early years of independence. In 1993, a corresponding reserve was established here, housed in a single building — the General Court House (also known as the house of Vasily Kochubey, the chief judge during the hetmanate of Ivan Mazepa).

By 2008, marking the 300th anniversary of the Batyrin tragedy, a program initiated by Viktor Yushchenko saw the reconstruction of the citadel of the destroyed fortress, and the reserve was granted national status. Grateful residents of Batyrin named a street leading to the reserve after the fourth president of Ukraine.

“We were bypassed by occupation, but we all heard and continue to hear”

In 2022, as Russian columns advanced towards Kyiv through the Chernihiv region, the former Cossack capital trembled constantly from explosions, yet it did not fall under enemy control.

Currently, sounds of Russian UAVs and missiles are audible from the neighboring towns of Konotop and Hlukhiv, but fortunately, Batyrin itself has not suffered from shelling. Recently, the city faced another disaster: the Russians poisoned the Siverskyi Donets River, leading to a significant fish die-off. Love recalls the stench that filled the city.

In the early days of the large-scale war, museum workers began hiding artifacts. They covered windows with film and placed sandbags near historical buildings to protect them from debris and fire. The wax figures of Ukrainian hetmans were concealed in the basement.

Initially, there were no tourists during the full-scale invasion, but by summer, things calmed down, and visitors began to return. By autumn 2022, “Hetman Capital” matched the number of guests as the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, which previously hosted the most visitors — over 1 million annually.

“In 2021, despite COVID-19 and everything else, we welcomed 177,000 visitors. The war, of course, affected this; it’s not even comparable. But last year, we had around 70,000 visitors. And that's not including our online exhibitions,” Love boasts.

Six employees of the reserve are currently defending the country — these include researchers, the deputy director, a security guard, and an electrician. All went to the front voluntarily.

“We constantly talked about Batyrin, but we were not understood. Now they understand”

Love leads us to the Church of the Resurrection of the Lord — a small wooden church located in the courtyard of the citadel. It was rebuilt alongside the fortress in 2008, and now church services are held here on major holidays, including the anniversary of the Batyrin tragedy.

Inside, sunlight falls on military flags hanging above portraits of fallen soldiers from the Batyrin community. With an emotional voice, she says: “These are now our heavenly warriors.”

When the Russians approached Batyrin in 1708 and invaded the city, parents tried to save their children by hiding them in the most fortified part of the fortress. Some civilians also took refuge here. However, when Menshikov's army stormed the city, the Russians showed no mercy and killed everyone hiding there, and the church was completely destroyed.

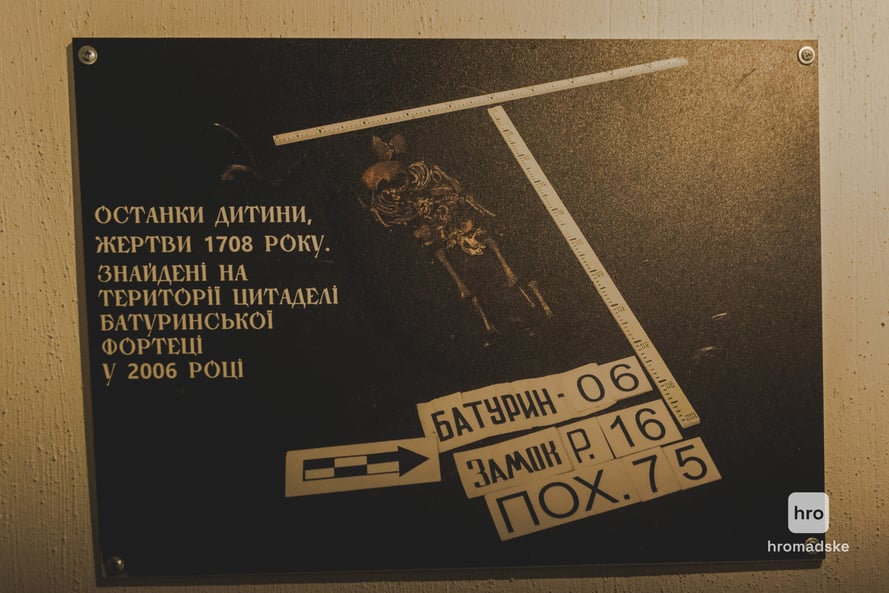

We descend into the crypt of the temple, where the remains of the slain Batyrin residents, including children, lie. Love points to a photo of remains found during excavations when the fortress was being rebuilt — the remains of a 14-year-old girl who was hiding from the fire in a grain pit. She died of asphyxiation.

Next to the graves, where the remains of the slain Batyrin residents rest, portraits of children hang, with two dates under each photo — their birth and death dates, the last dated 2022 and 2023. These are photographs of children killed by Russians after the onset of the full-scale invasion. The installation was symbolically named: “Yesterday Batyrin, and today — Bucha.”

“Many people found it hard to understand before the full-scale invasion. We constantly talked about the tragedy of Batyrin. We discussed all the tragic pages of history. But people did not understand. And when it repeated itself, many realized that the enemy remained the same, and their methods were the same as 300 years ago,” Love recounts.

“We want to find a mace, at least Mazepa's”

We exit the crypt into the street. Love leads us to a closed space that resembles a rural barn from the outside. This is an arsenal, where Cossack weapons were stored during the hetman era, and now it houses various military items. This installation opened in May, and some artifacts were also discovered this year.

Despite the ongoing war and proximity to the Russian border, archaeological excavations continue, with a pause in 2022-2023. However, the current expedition is the smallest ever conducted.

I ask if there is anything specific they hope to find but do not know where it is hidden:

“We want to find the hetman's mace,” Love replies, continuing: “We don’t know if it’s here or not, but we do know that currently, there are no hetman maces in Ukraine: neither Khmelnytsky's, nor Mazepa's, nor Samoylovych's. Every artifact is important to us.”

Where the hetman maces are now remains a mystery, but it is known that many valuable artifacts were taken from Batyrin (as well as from many other cities) to Russia. The most famous are the cannon “Lev,” which stands in the Kremlin, and Mazepa's bell. It was believed to have been destroyed, but in 2015, observant scholars spotted it in one of the monasteries in Russian Orenburg.

Next, we head to the house of hetman Ivan Mazepa, joking that it is like the Cossack Office of the President. Once, it was a majestic building, but in 1708, it was completely destroyed by Menshikov's Russian army.

We enter — there is an exhibition of wax figures of hetmans, some of which were retrieved from the basement where they were stored at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. I recognize all of them: Khmelnytsky, Vygovsky, Doroshen