Could nuclear weapons have remained in Ukraine? Volodymyr Viatrovych discusses Kravchuk's role, U.S. interests, and the Budapest Memorandum.

Why Disarmament Started in the First Place

From today's perspective, everything seems quite straightforward. Those who acted in the 1990s appear foolish and naive, and we think we would have done things differently. I believe one reason why Ukrainians acted the way they did in the early 1990s was their lack of historical knowledge. They did not want to remind themselves and the world that Russia has always been a dangerous enemy for Ukraine. Any attempts to consciously weaken themselves in front of Russia could prove to be extremely costly.

The rhetoric of many politicians in the early 1990s reminded me terribly of the rhetoric of Ukrainian politicians in the early 20th century. Recently, I watched a video featuring Leonid Kravchuk from 1994, where he confidently states that we, as a Ukrainian state, can actually lead the world in disarmament, showing everyone how it should be done. This strongly echoed the words of Volodymyr Vynnychenko in 1917-1918, who also believed that Ukraine was destined to be a leading representative of progress, ahead of the entire planet. At a time when the First World War was still ongoing and the armed struggle for independence was continuing, he declared: we will be different; we will show the world that disarmament is possible, that we do not need armies. Thus, we will change this world. This naivety, which unfortunately played a fateful role from 1917 to 1921, repeated itself in the 1990s.

On the World's Reaction

A lesson that should be reminded to ourselves and especially to the world concerns the reaction of the democratic, Western world to the processes occurring in the early 1990s during the collapse of the Soviet Union. In 1917-1921, the Russian Empire was collapsing, and the West feared the Bolsheviks, believing it necessary to stop them. However, instead of betting on the peoples attempting to build their independent states on the ruins of the Russian Empire, including Ukrainians, they chose to bet on the "good Russians." This turned out to be a catastrophic mistake because all the colossal resources the world poured into supporting the so-called White anti-Bolshevik Russian movement went to waste. They suffered a complete defeat.

Thus, in the 1990s, ignorance of history essentially led to a repetition of this lesson, as the democratic West celebrated its victory in the Cold War over the Soviet Union, but had one major fear: that the Soviet Union would collapse and nuclear weapons would spread across the world, making the horrors of the Cold War even worse. They thought: let's concentrate everything. And of course, Russia was perceived as the main and indeed the only partner with whom one could negotiate. This historical Russophilia manifested itself in the belief that all nuclear weapons should be concentrated in the hands of Russia to avoid a nuclear threat. Now, from the perspective of 2024, we can absolutely speak of the world's naivety regarding the decision to hand over weapons to the very state that is currently not hesitant to brandish its nuclear stick across the globe.

Why Ukrainian Politicians Acted This Way

We have no right to view the past solely from today's perspective. We cannot judge those who made decisions back then, knowing how everything turned out. Otherwise, we will only be satisfying our own arrogance: look how smart we are, while they were foolish for acting as they did.

In fact, if we delve deeper into the early 1990s, it becomes clear that the actions taken by the officials of that time, including Kravchuk and other politicians, were not arbitrary. They reflected the mood of society at that time.

It is essential to understand that by the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, the very words "atomic bomb," "nuclear energy," and everything associated with it evoked horror. Especially among Ukrainians, considering the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster. Therefore, the consensus was to shut down all nuclear power plants and remove everything related to nuclear weapons as quickly as possible. This was the prevailing public sentiment. The vast majority of Ukrainians thought this way. Moreover, when the disaster occurred, the Soviet authorities did everything to cover it up. The lack of truthful and complete information fostered even greater fears, and the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster were perceived as far worse than they actually were. Hence, society wanted nothing to do with this nuclear past. This is the first reason why the idea of getting rid of nuclear weapons was seen as acceptable at that time.

The second reason was that the politicians of that time, who were striving for independence, believed that Ukraine's possession of nuclear weapons could act as a deterrent against the recognition of Ukraine's independence. Therefore, acting essentially preemptively, they began promoting the thesis that "do not worry, we want to be independent, but we will not be a nuclear state; you will not have to deal with another menace in the form of another nuclear state, especially one with such a large potential of several thousand warheads, the third-largest nuclear potential in the world," and so on. This was an attempt to preemptively appeal to those who were to be Western partners.

Additionally, it should be noted that getting rid of nuclear weapons was also a global trend. This was the concluding phase of the Cold War. Everyone in the West was also afraid that someone would press the same terrifying red button, and missiles would fly. It is important to understand that this anti-nuclear, anti-atomic sentiment was not unique to Ukrainians. It was fashionable worldwide. For decades, there had been a nuclear psychosis where everyone feared the possible onset of nuclear war and prepared for shelter in bunkers. This atmosphere of fear began to ease precisely in the second half of the 1980s when negotiations began between Reagan and Gorbachev, and the world began to breathe a sigh of relief.

In this context, the theme of how great it is to get rid of nuclear weapons became fashionable. Heroes included Reagan and Gorbachev, who signed relevant international agreements. Thus, there was a desire among the figures of the Ukrainian national-democratic opposition movement, which sought to achieve Ukraine's independence, to ride this wave and turn it into a wave of support for Ukraine. Therefore, I categorically disagree with those who believe that the mere emergence of this idea of nuclear disarmament in Ukraine was some kind of sabotage against the country. No. In reality, it reflected the wave of that time.

One of the first to articulate this clearly at the political level was, unfortunately, the late international lawyer Volodymyr Vasylenko, one of the authors of the Declaration of Sovereignty. He was among those who believed that Ukraine's renunciation of nuclear status and weapons should be a powerful step toward Ukraine's independence, garnering support from the West. This thesis was supported by the national-democratic opposition at the time, represented by the People's Movement of Ukraine, and it was thanks to them that this thesis appeared in the Declaration of Sovereignty on July 16, 1990.

Here, the intentions were entirely noble. Moreover, they justified it further by stating that we need to declare Ukraine's non-nuclear status, which would be a step aiding Ukraine's independence, as a non-nuclear state cannot be part of a nuclear one, like the USSR. Accordingly, this was also a step toward independence. In hindsight, this thesis seems a bit naive, considering that there were many other Soviet republics that were never nuclear but remained part of the USSR until its collapse.

On Expectations and Reality

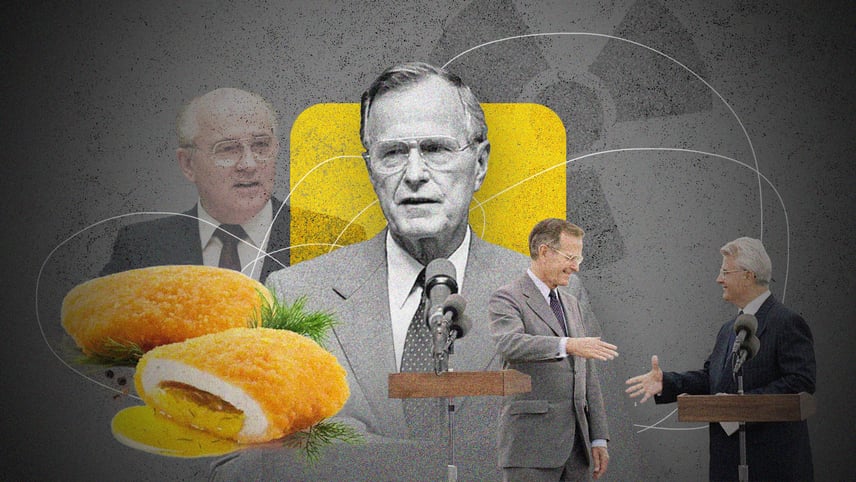

Unfortunately, the thesis "let's get rid of nuclear weapons, and you will recognize our independence" did not resonate in the West. In 1990, Margaret Thatcher visited Kyiv and stated that for her, an independent Ukraine was something akin to an independent California. In the summer of 1991, George H.W. Bush, who was in Kyiv, also believed that independence could be harmful for Ukraine, so he cautioned that freedom does not equal some harmful nationalism, which you do not need, famously known as the Chicken Kiev speech.

Moreover, when Ukraine proclaimed its independence on August 24, 1991, the idea that further steps to rid itself of nuclear status would supposedly facilitate its recognition did not work out. Already in October 1991, the Verkhovna Rada adopted a special resolution reaffirming Ukraine's non-nuclear status. This did not change the attitude of most Western countries, which were still waiting to decide whether to recognize Ukraine as an independent state or not. The situation turned around with the referendum on December 1, 1991, when over 90% of Ukrainians voted in favor of independence. Following this, Poland was the first, Canada the second, and then the United States recognized Ukraine as an independent state.

However, the West decided to exploit the sentiments present in Ukrainian society. Unfortunately, relying on their faith in a good Russia, into which they poured colossal economic resources, they believed that launching a market economy in Russia would mean that it would become a good democratic state, especially with a strong democrat like Boris Yeltsin at the helm, thus becoming our partner. It should be understood that the West, in the early 1990